I used to be too subjective, and I was always tempted to find my inner self in the exterior and dissipate my imagination on other people and on life. (Oskar Kokoschka)

Oskar Kokoschka, Knight Errant (Self-Portrait), 1915

Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980) was born Pöchlarn, Lower Austria. He studied at the "Wiener Kunstgewerbeschule" (Vienna School of Arts and Crafts) from 1905 to 1908. Kokoschka soon became one of the most important painters of expressionist art. After the "Kunstschau 1908" (Art Show 1908), Adolf Loos became one of his promoters, and Klimt even called Kokoschka the greatest talent of the young generation. Kokoschka's book "Die träumenden Knaben", published in 1908, was dedicated to Gustav Klimt. Originally staged in Vienna in 1909, Kokoschka's Murderer, The Hope of Women is generally regarded as the first Expressionist theatre play. As an early exponent of the avant-garde expressionist movement, he began to paint psychologically penetrating portraits of Viennese physicians, architects and artists, like this one of Adolf Loos:

Oskar Kokoschka, Portrait of Adolf Loos, 1909

In 1912 Alma Mahler (former wife of composer Gustav Mahler) met the young painter, who was known as the enfant terrible of the Viennese art scene. Kokoschka was violent and unbridled, and the press derided him as "the wildest beast of all". Their liaison led on to an unrestrained amour fou, and Kokoschka´s consuming passion was soon transformed into subjugation, his jealousy into obsession. Kokoschka´s mother rushed to her son´s assistance and wrote to Alma: "If you see Oskar again, I´ll shoot you!" One of Kokoschka´s most famous paintings, "Die Windsbraut", testifies to this anguished time:

Oskar Kokoschka, Die Windsbraut (The Bride of the Wind), 1914. This painting shows Kokoschka and Alma Mahler as a shipwrecked pair in stormy seas. "He satisfied my life and he destroyed it", she said.

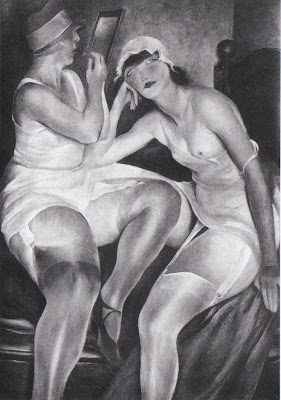

After their separation, Kokoschka volunteered for World War I, where he received a serious bayonet injury in Russia and a head shot in Galicia. In 1916, Kokoschka served as a war painter at the Italian Isonzo front, was diagnosed as "mentally unstable", and, in 1917, left Vienna for Dresden where he had received a professorship at the Art Academy until 1924. News of Alma´s marriage to architect Walter Gropius hurt him so much that, in deepest desperation, he ordered a life-size doll from a doll-maker in Munich which should resemble Alma in every detail, because he thought the artefact would console him for the final loss of his lover. Not surprisingly, the result was disappointing: a clumsy construction of fabric and wood-wool, which Kokoschka displayed at a wild party in his atelier in Dresden, in 1919.

Oskar Kokoschka, Self-Portrait with Doll, 1922

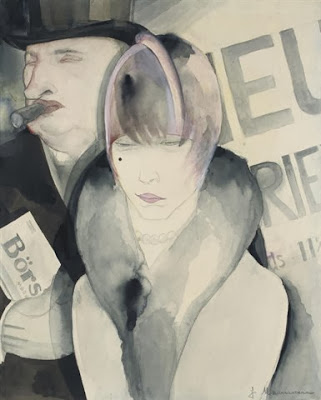

Kokoschka's professorship in Dresden ended in 1924 and was followd by a seven-year period of travel in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East resulting in a number of robust, brilliantly coloured landscapes and figure pieces, painted with great freedom and exuberance. Many of them are views of harbours, mountains, and cities. Examples from this period include View of Cologne, Tower Bridge and Harbour of Marseilles:

Oskar Kokoschka, The Harbour of Marseille, 1925

In 1931 Kokosschka returned to Vienna where he was commissioned by the Vienna City Administration to paint a Viennese motive. (He chose the view of Vienna from Wilhelminenberg). In 1934, due to the worsening political situation in Germany and Austria, Kokoschka moved to Prague where he was appointed professor at the Art Academy. His works were exhibited as "degenerate art" in the Third Reich which "motivated" Kokoschka to produce the following self-portrait:

Oskar Kokoschka, Self-Portrait as a Degenerate Artist, 1937

In 1938, when the Czechs began to mobilize for the expected invasion of the German Wehrmacht, Kokoschka fled to England and remained there during the war. In England, he produced his famous war paintings during World War II. Kokoschka became a British citizen in 1946 and only in 1978 would regain Austrian citizenship. He traveled briefly to the United States in 1947 before settling in Switzerland, where he lived the rest of his life. Oskar Kokoschka died 1980 in Montreux.

Oskar Kokoschka, The Red Egg, 1940

Kokoschka had much in common with his contemporary Max Beckmann. Both maintained their independence from German Expressionism, yet they are now regarded as its supreme masters, who delved deeply into the art of past masters to develop unique individual styles. Both wrote eloquently of the need to develop the art of "seeing" (Kokoschka emphasized depth perception while Beckmann was concerned with mystical insight into the invisible realm), and both were masters of innovative oil painting techniques anchored in earlier traditions.

Oskar Kokoschka, Prague, Nostalgia, 1938. This was the first painting Kokoschka completed in London, after fleeing Czechoslovakia in 1938. Painted from memory, it features the famous view of Prague with the old Charles Bridge and cathedral in the background.

You can see more works of Oskar Kokoschka here on my Flickr page.

You can see more works of Oskar Kokoschka here on my Flickr page.